Experimental Highlights - 2017

August

Turbulent Dynamo Experiment Yields ‘Amazing’ Data

NIF’s Night Owls: Where the Wild Things Are

From sunset to sunrise, while others slumber, the Owls of the National Ignition Facility nurture the world’s most energetic laser through some of its most productive hours.

On this particular summer night, Shot Director Steve Weaver is the Owl Shift leader of 16 scientists, engineers, and technicians who keep the massive physics experiment humming, working to create temperatures of up to 100 million degrees and pressures as much as 100 billion times Earth’s atmosphere, for a 13-hour extended shift.

Darkness descends on the facility as the NIF Owls begin their shift. Photos: Jason Laurea

Darkness descends on the facility as the NIF Owls begin their shift. Photos: Jason Laurea To fully explore the unprecedented capabilities of NIF’s 192 lasers, the 10-story tall facility runs virtually around the clock. On a laser capable of producing 500 trillion watts—or 1,000 times more power than the United States uses at any instant in time—some of the most powerful and important shots have been reached on the Owl Shift.

“It’s an interesting way to move about the world, being so awake and productive while most everyone you know is asleep,” Weaver observes. “You see so many new things and experiences.”

The world of NIF’s Owls dates back to December 2002. While the daytime hours were spent on building the facility and installing the equipment, nighttime became reserved for commissioning the laser, according to NIF Operations Manager Bruno Van Wonterghem.

This practice continued into early facility operations and by October 2010, the Owl Shift was born, bringing NIF into nearly perpetual activity to maximize return on the nation’s investment in the facility. “We started expanding NIF shifts into night and early morning hours because of the importance of our missions in Stockpile Stewardship, national security and Discovery Science,” Van Wonterghem says. As with other major scientific facilities operated by the U.S. Department of Energy, shot time on NIF is in high demand by scientists from across the country and around the world competing to take advantage of the facility’s unique capabilities.

Layton Travis (right) briefs Owl Shift Control Room Operator Thomas Morris-Martin on the highlights of the previous shift. During the day-to-night turnover each worker meets with his or her counterpart to discuss the transition, like nurses handing over hospital patients.

Layton Travis (right) briefs Owl Shift Control Room Operator Thomas Morris-Martin on the highlights of the previous shift. During the day-to-night turnover each worker meets with his or her counterpart to discuss the transition, like nurses handing over hospital patients. And so came the Owls, on duty Sunday through Friday nights (Owls get four days off for every three days worked). On Friday days, Saturdays, and Sunday days, the lasers rest while the NIF facility staff utilizes that time for maintenance and reconfiguration.

Owls work with a smaller core staff than NIF’s standard day-side crew. That can present challenges, say team members—such as the need to call a NIF operations manager at 2 a.m. to report a problem—and advantages, like greater autonomy. For example, novice laser tech Micah Bewley points to the revised shot checklist that he had a hand in improving.

Plus, the Owls get a rare view of the wild side of the 65-year-old Laboratory in the foothills by the Altamont Pass with its dramatic windmills, where night-prowling creatures like foxes roam free. Brent Blue, NIF Nuclear Security Applications program manager, used to love the wild side of Owl Shift, “until,” he says with a sour face, “I surprised a skunk one night.”

Looking to the Future

Alignment Operator Cody Athans finds the night-shift pace absorbing; “You can focus more on the work and the job,” he says.

Motivation comes easier for him at NIF, Athans says, because he sees the technology of inertial confinement fusion as the future after spending his early youth working in the fossil-fuel industry in his native Houston, feeling stuck in the past.

“Now I align the world’s most energetic laser for a living,” he says with quiet pride as he works the digital controls on his console in the NIF Control Room. A crisply defined image on the screen shows a laser target easing into place on the mechanical arm of the target positioner (TarPos), one of three roughly 8.5-meter (27 foot)-long positioners in the Target Chamber. Helping Athans with that future-feeling vibe is the high-tech Control Room itself—clean, spare, airy, and designed in consultation with the space-age expertise of NASA.

Earlier in the Owl Shift, Weaver headed to the inner sanctums of the facility to observe and approve installation of the target to be used for the first shot of the night.“We always have multiple layers of redundancy to ensure correct procedure execution in NIF,” he explains.

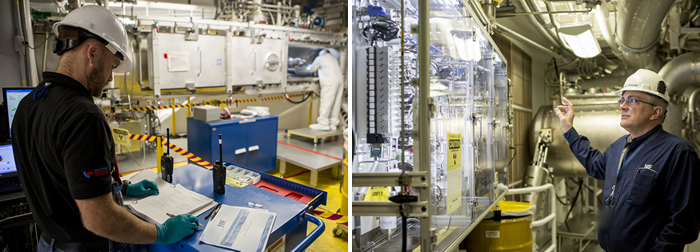

(Left) Derek Brangham follows a procedure checklist as a technician in the background installs a target in a target positioner. (Right) Shot Director Steve Weaver checks the configurations and pressures of the target gas manifolds that supply fill gas to NIF targets. Strict protocols are followed for every firing of the laser.

(Left) Derek Brangham follows a procedure checklist as a technician in the background installs a target in a target positioner. (Right) Shot Director Steve Weaver checks the configurations and pressures of the target gas manifolds that supply fill gas to NIF targets. Strict protocols are followed for every firing of the laser. For each target check, Weaver zips through the well-ordered passageways to the TarPos, where the tube of the robotic positioner is pulled back and opened. Cleanroom-suited technicians await him with clipboards and checklists that he inspects and reads through as a technician installs the target with slow-motion care into the sliding door, secures it, photographs it in place, and slides it back into the vessel. Then Weaver zooms back to the Control Room, moving like a man who believes in wasting no time when it comes to supporting the nation’s security and the National Nuclear Security Administration’s Stockpile Stewardship Program.

Back in the Control Room, Lead Operator Dean Felzkowski sits at his microphone delivering commands. The crew follows the almost-military protocol of the operations, down to their classy NIF navy blue collared shirts. Felzkowski is a veteran of laser technology, and like many of the previous generation of managers, he worries that it will be difficult to find qualified photonics practitioners in the future, with the growing high-tech industry raiding the field while training schools keep dwindling.

The current NIF laser techs took many different paths to arrive on the Owl Shift. Some knew of the opportunities in lasers and deliberately pursued degrees in laser optics; some came through the military; and still others trained on the job—like Alton Huey, who started at the Lab in 2002 in electronics engineering and transferred over to working on NIF lasers.

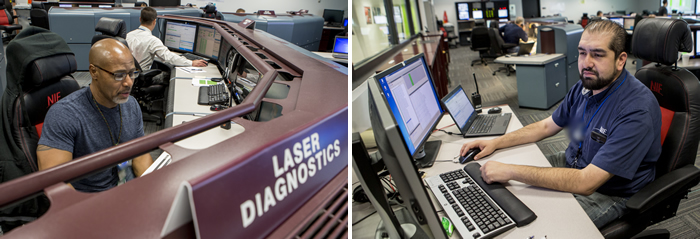

At work in the NIF Control Room, diagnostics technician Alton Huey (left) finds job satisfaction in the challenges and importance of NIF’s missions; while software technician Jesus Garcia appreciates the normally calm pace of the Owl Shift compared to the sometimes crisis atmosphere found on IT support desks.

At work in the NIF Control Room, diagnostics technician Alton Huey (left) finds job satisfaction in the challenges and importance of NIF’s missions; while software technician Jesus Garcia appreciates the normally calm pace of the Owl Shift compared to the sometimes crisis atmosphere found on IT support desks. Like their noctournal namesakes, Huey and the NIF Owls spend their hours in mostly solitary toil. They meticulously prep for hours for a laser shot that lasts only a few billionths of a second. The laser beams travel one kilometer through the laser bays at almost 300,000 kilometers a second, fast enough to circle the globe twice in the blink of an eye.

And that’s a challenge Huey is proud to meet, to help the team save a shot whenever possible from being scrubbed. Missed shots are missed scientific opportunities and can delay experiments for weeks or months.

“When the scientist comes back and tells you, ‘Hey, we got great results,’ or ‘Hey, you did a good job,’ it feels good being part of that,” said Huey. “No matter what time it happens, or how it happens, we’re part of history—that’s how important the NIF facility is.”

For the ultimate in high-tech facilities, NIF does have its low-tech customs. At the start of each Owl Shift someone brings in cookies. “We must have an offering to the laser gods,” jokes laser technician Miguel Munguia, who tops his NIF uniform with local style, a San Francisco Giants ballcap.

Later in the evening, the Owl Shift encounters a mechanical problem with the beam control line. The technicians calmly walk through the procedures on their checklist. The problem escalates. Phone calls are made. The experiment scheduled for 1:00 a.m. gets pushed back to 2:00 a.m.

An Open Window

By the time of this Owl Shift, scientist Amy Jenei had been waiting nearly a year for her scheduled experiment. She explains ruefully that her first crack at the experiment in February—that she had already waited months for—had to be postponed. When the rescheduled experiment in the spring was again pushed off the schedule, she asked Weaver to call her, no matter what the time, so she could come in to oversee preparations and confirm the target alignment.

After 2:15 a.m., Jenei arrives in the Control Room; this is the window for her experiment, and she wasn’t going to lose it without a fight. Soon the NIF mechanical systems are humming back on track, the alignment operators position the target to Jenei’s satisfaction, and the countdown begins as horns and loudspeakers boom throughout the NIF facility announcing the impending shot.

“All the great science happens at night.”

–Amy Jenei

Jenei’s experiment is part of a high-energy-density materials campaign to measure the equation of state of boron at very high pressures, using a platform originally developed at NIF through a Discovery Science campaign.

“What’s exciting,” she says, “is the platform allows us the capability to make equation-of-state measurements to higher pressure than any other experimental platform anywhere. With NIF, we’re able to get to the gigabar pressure regime (billions of Earth atmospheres), which is an order of magnitude higher than any other measurements.”

She has high hopes that her experiment this night will break new ground by validating data in a high pressure/temperature regime where the equation-of-state models of how materials behave currently are based purely on extrapolations and a few untested physics models. “This kind of experiment for the first time really allows us to benchmark those equation-of-state models,” she says.

The shot is finished at 2:27 a.m.

While Jenei continues to work on her laptop, downloading the raw data for a first look, the Owl Shift team starts working to set up another shot for later that morning.

“Physicists will come in anytime,” Jenei says, “because they’ve been planning their experiments for months. They’re passionate, they’re interested, they’ll come in any time of the day or night.” She considers it no hardship to work through the dead of night if doing so earns her shot time on NIF. “My impression of NIF is all the great science happens at night,” she says.

By 6:30 a.m. the next shift has assembled in NIF for the pre-shift briefing and turnover discussion. With 13 hours of work having been performed on Owl Shift, there’s a lot of ground to cover. The turnover completed, the Owls head out into the the light of early dawn, their duty to NIF, and to science and national security, completed for another day.

Turbulent Dynamo Experiment Yields ‘Amazing’ Data

The first NIF Discovery Science experimental campaign to use the facility’s new Optical Thomson Scattering (OTS) detector was successfully completed on Aug. 15.

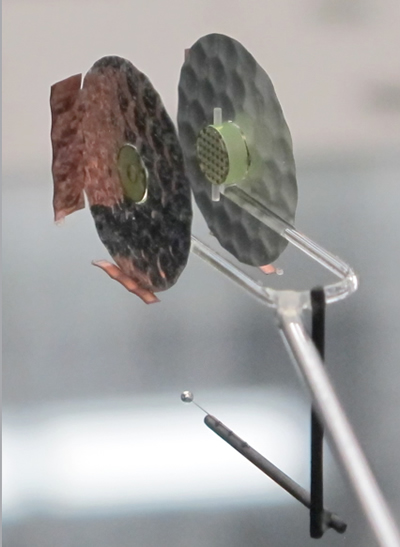

A target used in the Aug. 15 turbulent dynamo campaign.

A target used in the Aug. 15 turbulent dynamo campaign. Discovery Science Program Leader Bruce Remington noted that University of Oxford professor Gianluca Gregori, the external principal investigator of the turbulent dynamo, or TDyno, experiments, is using NIF to uncover how the universe creates the huge intergalactic magnetic fields found throughout the universe (see “Probing the Mysteries of Cosmic Magnetic Fields”).

The TDyno researchers employed the OTS diagnostic under the guidance of Steve Ross, the LLNL liaison scientist for the campaign and the OTS diagnostic responsible scientist.

Shot responsible individual Jena Meinecke, a junior research fellow at the University of Oxford, tweeted that the experiment produced “amazing” Thomson scattering data and the new diagnostic capability “will hugely benefit the HEDP (high energy density physics) community.”

In the three-shot campaign, completed in a little more than 24 hours, laser ablation of two plastic disks generated turbulent counter-streaming plasma flows. The flows became turbulent as they passed through two plastic grids and generated strong turbulence at the interaction region of the flows, where dynamo can reign. A deuterium-helium-3-filled “exploding pusher” backlighter capsule below the target was used in conjunction with a large-area proton detector to image the magnetic fields.

Ross reported that the laser, diagnostics, and target all performed as required and the desired plasma conditions likely were achieved. Careful data analysis will show the degree to which turbulent magnetic field amplification resulted.