World’s Largest Optical Lens Shipped to SLAC

When the world’s newest telescope starts imaging the southern sky in 2023, it will take photos using optical assemblies designed by scientists and engineers from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), including NIF, and built by Lab industrial partners.

A key feature of the camera’s optical assemblies for the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST), under construction in northern Chile, will be its three lenses, one of which at 1.57 meters (5.1 feet) in diameter is believed to be the world’s largest high-performance optical lens ever fabricated.

The lens assembly, which includes the lens dubbed L-1, and its smaller companion lens (L-2), at 1.2 meters in diameter, was built over the past five years by Boulder, Colorado-based Ball Aerospace and its subcontractor, Tucson-based Arizona Optical Systems.

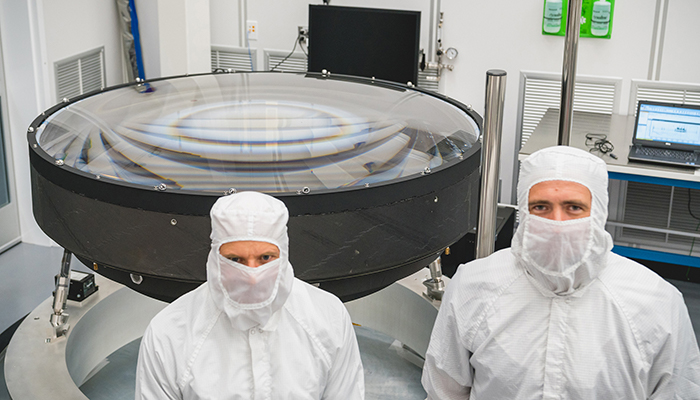

LLNL engineer Vincent Riot (left), who has worked on the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST) for more than a decade and has been the full camera project manager since 2017, and LLNL optical engineer Justin Wolfe, the LSST camera optics subsystems manager, stand in front of the LSST main lens assembly. Credit:Farrin Abbott/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

LLNL engineer Vincent Riot (left), who has worked on the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST) for more than a decade and has been the full camera project manager since 2017, and LLNL optical engineer Justin Wolfe, the LSST camera optics subsystems manager, stand in front of the LSST main lens assembly. Credit:Farrin Abbott/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory Mounted together in a carbon fiber structure, the two lenses were shipped from Tucson, arriving intact after a 17-hour truck journey at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in Menlo Park.

SLAC is managing the overall design and fabrication, as well as the subcomponent integration and final assembly of LSST’s $168 million, 3,200-megapixel digital camera, which is more than 90 percent complete and due to be finished by early 2021. In addition to SLAC and LLNL, the team building the camera includes an international collaboration of universities and labs, including the Le Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique in Paris and Brookhaven National Laboratory.

“The success of the fabrication of this unique optical assembly is a testament to LLNL’s world-leading expertise in large optics, built on decades of experience in the construction of the world’s largest and most powerful laser systems,” said physicist Scot Olivier, who helped manage Livermore’s involvement in the LSST project for more than a decade.

Olivier said without the dedicated and exceptional work of LLNL optical scientists Lynn Seppala and Brian Bauman and LLNL engineers Vincent Riot, Scott Winters and Justin Wolfe, spanning a period of nearly two decades, the LSST camera optics, including the world’s largest lens, would not be the reality they are today.

“Riot’s contributions to LSST also go far beyond the camera optics — as the current overall project manager for the LSST camera, Riot is a principal figure in the successful development of this major scientific instrument that is poised to revolutionize the field of astronomy,” Olivier added.

Riot and Bauman also credited the work of LLNL engineers Darrell Carter, Simon Cohen, Pete Fitsos, Steve Pratuch, and John Taylor.

Livermore involvement in LSST started around 2001, spurred by the scientific interest of LLNL astrophysicist Kem Cook, a member of the Lab team that previously led the search for galactic dark matter in the form of Massive Compact Halo Objects.

However, LLNL participation in LSST quickly became centered on the Lab’s expertise in large optics, built over decades of developing the world’s largest laser systems. Starting in 2002, Seppala, who helped design NIF, made a series of improvements to the optical design of LSST leading to the 2005 baseline design.

This consisted of three mirrors, the two largest in the same plane so they could be fabricated from the same piece of glass, and three large lenses, as well as a set of six filters that define the color of the images recorded by the 3.2-gigapixel camera detector.

LSST Director Steven Kahn, a physicist at Stanford University and SLAC, noted that “Livermore has played a very significant technical role in the camera and a historically important role in the telescope design.”

Livermore’s researchers made essential contributions to the optical design of LSST’s lenses and mirrors, the way LSST will survey the sky, how it compensates for atmospheric turbulence and gravity, and more.

LLNL personnel led the procurement and delivery of the camera’s optical assemblies, which include the three lenses (the third lens, at 72 centimeters in diameter, will be delivered to SLAC within a month) and a set of filters covering six wavelength-bands, all in their final mechanical mount.

Livermore focused on the design and then delegated fabrication to industry vendors, although the filters will be placed into the interface mounts at the Lab before being shipped to SLAC for final integration into the camera.

The 8.4-meter LSST will take digital images of the entire visible southern sky every few nights, revealing unprecedented details of the universe and helping unravel some of its greatest mysteries. During a 10-year time frame, LSST will detect about 20 billion galaxies — the first time a telescope will observe more galaxies than there are people on Earth — and will create a time-lapse “movie” of the sky.

This data will help researchers better understand dark matter and dark energy, which together make up 95 percent of the universe, but whose makeup remains unknown, as well as study the formation of galaxies, track potentially hazardous asteroids and observe exploding stars.

The telescope’s camera — the size of a small car and weighing more than three tons — will capture full-sky images at such high resolution that it would take 1,500 high-definition television screens to display just one picture.

Research scientists aren’t the only ones who will have access to the LSST data. Anyone with a computer will be able to fly through the universe, past objects 100 million times fainter than can be observed with the unaided eye. The LSST project will provide an engagement platform to enable both students and the public to participate in the process of scientific discovery.

Riot, who started on the LSST project in 2008, initially managed the camera optics fabrication planning, became the LSST deputy camera manager in 2013 and the full camera project manager in 2017. For the past three years, he has worked at LLNL and at SLAC on special assignment.

The dual-mirror monolith in LSST has also inspired Riot and Bauman to seek novel design forms for nanosatellite telescopes.

“There are important challenges getting everything together for the LSST camera. We’re receiving all of these expensive parts that people have been working on for years and they all have to fit together,” Riot said.

Wolfe, an LLNL optical engineer and the LSST camera optics subsystems manager, and Riot are pleased that the world’s largest optical lens has overcome hurdles.

“Any time you undertake an activity for the first time, there are bound to be challenges, and production of the LSST L-1 lens proved to be no different,” Wolfe said. “Every stage was crucial and carried great risk. You are working with a piece of glass more than five feet in diameter and only four inches thick. Any mishandling, shock or accident can result in damage to the lens. The lens is a work of craftsmanship and we are all rightly proud of it.

“When I joined LLNL I had no idea that it would lead to the opportunity to deliver first-of-a-kind optics to a first-of-a-kind telescope,” Wolfe said.“From production of the largest precision lens known, to coating of the largest precision bandpass filters, the LSST optics have set a new standard.”

Construction on LSST started in 2014 on El Peñon, a peak 8,800 feet high along the Cerro Pachón ridge in the Andes Mountains, located 220 miles north of Santiago, Chile.

Financial support for LSST comes from the National Science Foundation (NSF), the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, and private funding raised by the LSST Corporation. The NSF-funded LSST Project Office for construction was established as an operating center under management of the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy. The DOE-funded effort to build the LSST camera is managed by the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

The camera system for LSST, including the three lenses and six filters designed by LLNL researchers and built by Lab industrial partners, will be shipped from SLAC to the telescope site in Chile in early 2021.

—Stephen Wampler

Follow us on Twitter: @lasers_llnl