Researchers Design a Compact High-Power Laser Using Plasma Optics

August 18, 2022

LLNL researchers have designed a compact multi-petawatt laser that uses plasma transmission gratings to overcome the power limitations of conventional solid-state optical gratings. The design could enable construction of an ultrafast laser up to 1,000 times more powerful than existing lasers of the same size.

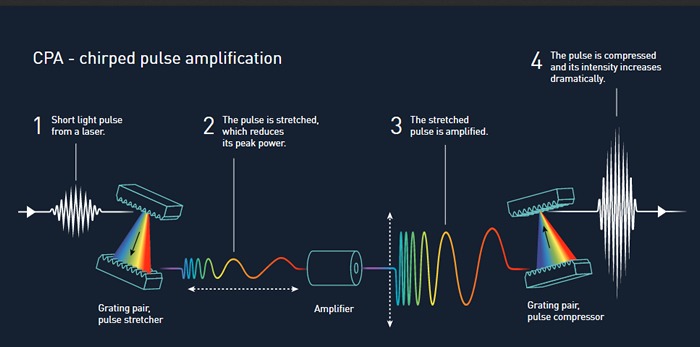

Petawatt (quadrillion-watt) lasers rely on diffraction gratings for chirped-pulse amplification (CPA), a technique for stretching, amplifying, and then compressing a high-energy laser pulse to avoid damaging optical components. CPA, which won a Nobel Prize in physics in 2018, is at the heart of NIF’s Advanced Radiographic Capability as well as NIF’s predecessor, the Nova laser, the world’s first petawatt laser.

The chirped-pulse amplification technique makes it possible for a petawatt laser’s high-power pulses to pass through laser optics without damaging them. Before amplification, low-energy laser pulses are passed through diffraction gratings to stretch their duration by as much as 25,000 times. After amplification, the pulses are recompressed back to near their original duration. Because the pulses pass through laser optics when they are long, they cause no damage. Credit: The Nobel Committee for Physics High Resolution Image

The chirped-pulse amplification technique makes it possible for a petawatt laser’s high-power pulses to pass through laser optics without damaging them. Before amplification, low-energy laser pulses are passed through diffraction gratings to stretch their duration by as much as 25,000 times. After amplification, the pulses are recompressed back to near their original duration. Because the pulses pass through laser optics when they are long, they cause no damage. Credit: The Nobel Committee for Physics High Resolution Image With a damage threshold several orders of magnitude higher than conventional reflection gratings, plasma gratings “allow us to deliver a lot more power for the same size grating,” said former LLNL postdoc Matthew Edwards, co-author of a Physical Review Applied paper describing the new design published online on Aug. 9. Edwards was joined on the paper by Laser-plasma Interactions Group Leader Pierre Michel.

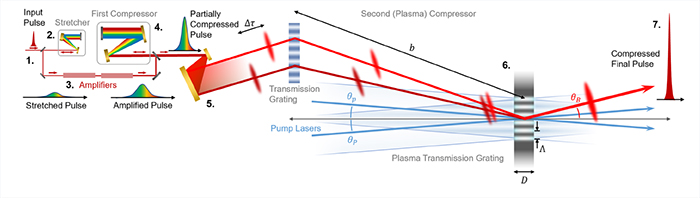

“Glass focusing optics for powerful lasers must be large to avoid damage,” Edwards said. ”The laser energy is spread out to keep local intensity low. Because the plasma resists optical damage better than a piece of glass, for example, we can imagine building a laser that produces hundreds or thousands of times as much power as a current system without making that system bigger.”  Schematic of a plasma-grating-based laser system using a double-compression architecture to compensate for the low angular dispersion of the plasma grating. The final grating (D) is formed in a plasma by two short-pulse beams from pump lasers. An input femtosecond (quadrillionth of a second) pulse from an oscillator is stretched, amplified, and compressed to 1-10 picoseconds (trillionths of a second) by the first stage (solid-state) compressor. Compression from 1-10 ps to 10-50 fs occurs in the second stage, where only the plasma grating sees a pulse duration shorter than 1 ps and the concomitant high intensity.

Schematic of a plasma-grating-based laser system using a double-compression architecture to compensate for the low angular dispersion of the plasma grating. The final grating (D) is formed in a plasma by two short-pulse beams from pump lasers. An input femtosecond (quadrillionth of a second) pulse from an oscillator is stretched, amplified, and compressed to 1-10 picoseconds (trillionths of a second) by the first stage (solid-state) compressor. Compression from 1-10 ps to 10-50 fs occurs in the second stage, where only the plasma grating sees a pulse duration shorter than 1 ps and the concomitant high intensity.

LLNL, with 50 years of experience in developing high-energy laser systems, has also been a long-time leader in the design and fabrication of the world’s largest diffraction gratings, such as the gold gratings used to produce 500-joule petawatt pulses on the Nova laser in the 1990s. Still larger gratings, however, would be required for next-generation multi-petawatt and exawatt (1,000-petawatt) lasers to overcome the limits on maximum fluence (energy density) imposed by conventional solid optics (see “Holographic Plasma Lenses for Ultra-High-Power Lasers”).

Edwards noted that optics made of plasma, a mixture of ions and free electrons, are “well suited to a relatively high-repetition-rate, high-average-power laser.” The new design could, for example, make it possible to field a laser system similar in size to the L3 HAPLS (High-Repetition Rate Advanced Petawatt Laser System) at ELI Beamlines in the Czech Republic, but with 100 times the peak power.

The L3-HAPLS at ELI Beamlines Research Center in the Czech Republic. Credit: ELI Beamlines

The L3-HAPLS at ELI Beamlines Research Center in the Czech Republic. Credit: ELI Beamlines Designed and constructed by LLNL and delivered to ELI Beamlines in 2017, HAPLS was designed to produce 30 joules of energy in a 30-femtosecond (quadrillionth of a second) pulse duration, which is equal to a petawatt, and do so at 10 Hertz (10 pulses per second).

“If you imagine trying to build HAPLS with 100 times the peak power at the same repetition rate—that is the sort of system where this would be most suitable,” said Edwards, now an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at Stanford University.

“The grating can be remade at a very high repetition rate, so we think that 10 Hertz operation is possible with this type of design. However, it would not be suitable for a high-average-power continuous-wave laser.”

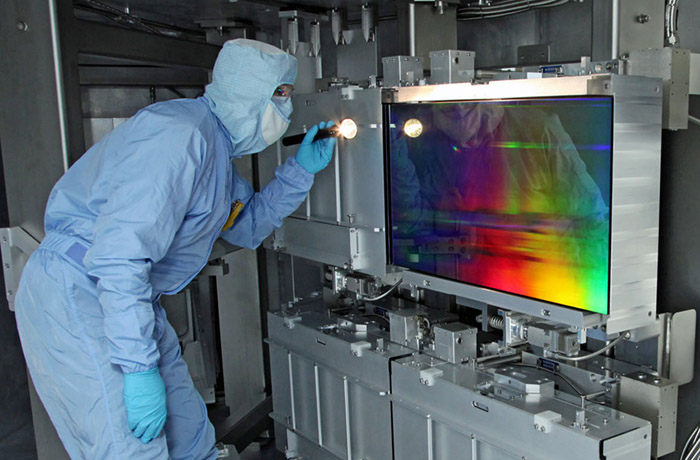

Engineer JB McLeod inspects one of the high-efficiency diffraction gratings installed in NIF’s Advanced Radiographic Capability (ARC) compressor vessel. ARC’s one-meter-wide multilayer dielectric gratings were specially developed at LLNL to withstand the record levels of energy generated by NIF’s lasers. Simulations suggest that the meter-scale final grating for a 10-petawatt laser could be replaced by a 1.5-millimeter-diameter plasma grating, allowing compression to, for example, 22 femtoseconds with 90 percent efficiency and providing a path towards compact multi-petawatt laser systems.

Engineer JB McLeod inspects one of the high-efficiency diffraction gratings installed in NIF’s Advanced Radiographic Capability (ARC) compressor vessel. ARC’s one-meter-wide multilayer dielectric gratings were specially developed at LLNL to withstand the record levels of energy generated by NIF’s lasers. Simulations suggest that the meter-scale final grating for a 10-petawatt laser could be replaced by a 1.5-millimeter-diameter plasma grating, allowing compression to, for example, 22 femtoseconds with 90 percent efficiency and providing a path towards compact multi-petawatt laser systems. While plasma optics have been used successfully in plasma mirrors, the researchers said, their use for pulse compression at high power has been limited by the difficulty of creating a sufficiently uniform large plasma and the complexity of nonlinear plasma wave dynamics.

“It has proven difficult to get plasmas to do what you want them to do,” Edwards said. “It’s difficult to make them sufficiently homogenous, to get the temperature and density variations to be small enough, and so on.

“We’re aiming for a design where that kind of inhomogeneity is as small a problem as possible for the overall system—the design should be very tolerant to imperfections in the plasma that you use.”

The researchers studied two plasma mechanisms: spatially varying ionization (SVI), in which variations in laser intensity create static regions of ionized and non-ionized gas; and ion-density fluctuations that occur in the plasma as electrons and ions are forced from areas of high laser intensity to areas of lower intensity (ponderomotively driven ion structures).

“Although plasmas are extremely damage resistant,” they said, “every plasma mechanism has a maximum tolerable intensity and energy flux before diffraction efficiency drops or the probe pulse becomes distorted. However, even with these limits, plasma gratings can operate at intensities almost six orders of magnitude higher than solid-state conventional gratings.”

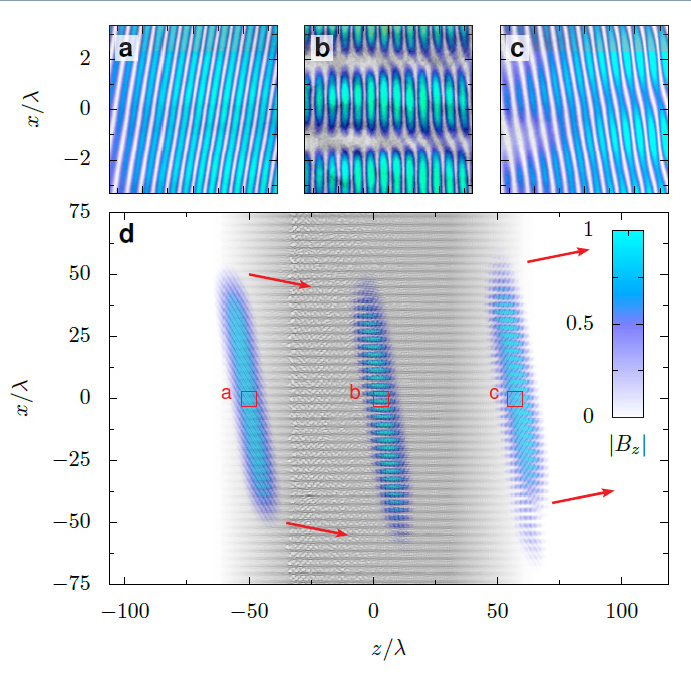

The researchers used a particle-in-cell (PIC) code called EPOCH to simulate the high-intensity performance of an ion ponderomotive grating as an example plasma-based final stage optic.

Based on the simulations, the researchers said, “we expect that this approach is capable of providing a degree of stability not accessible with other plasma-based compression mechanisms, and may prove more feasible to build in practice.” The new design “needs only gas as the initial medium, is robust to variations in plasma conditions, and minimizes the plasma volume to make sufficient uniformity practical.

“By using achievable plasma parameters and avoiding solid-density plasma and solid-state optics, this approach offers a feasible path towards the next generation of high-power laser.”

The research was supported in part by LLNL’s Laboratory Directed Research and Development (LDRD) Program.

More Information:

“Plasma Gratings for High-Power Lasers,” Physics, August 9, 2022

“Holographic Plasma Lenses for Ultra-High-Power Lasers,” NIF & Photon Science News, March 14, 2022

“LLNL Constructing High-Power Laser for New Experimental Facility at SLAC,” NIF & Photon Science News, March 9, 2022

“Lasers Without Limits,” Science & Technology Review, July, 2021

“New Gratings Promise 20 Percent Performance Boost for Ultrafast Lasers,” NIF & Photon Science News, October 15, 2019

“Plasma Optic Combines NIF Lasers into ‘Superbeam,’” NIF & Photon Science News, October, 2017

—Charlie Osolin

Follow us on Twitter: @lasers_llnl