NIF & PS People - 2018

December

Looking Back on a Mammoth Discovery

Inspiring Science Careers Through STEM Stories

Last month LLNL’s Office of Strategic Diversity and Inclusion Programs (OSDIP) hosted more than 180 middle school students for STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) Day. They came from classrooms from south of Modesto to Sacramento for exposure to the exciting research and innovation happening across the Lab (see “Central Valley Students Inspired by STEM Day”).

Inside NIF’s lobby, STEM Day docent and graphics designer John Jett discusses the role of art in science and technology communications. Photos by Mark Meamber

Inside NIF’s lobby, STEM Day docent and graphics designer John Jett discusses the role of art in science and technology communications. Photos by Mark Meamber When the students arrived at NIF, they received more than a dose of science and technology. They heard from scientists, engineers, and support staffers about what it really takes to run the world’s largest and most energetic laser: all kinds of people doing all kinds of jobs. But how did these people ever find their way to NIF? The answer: many diverse ways.

“We tried something a little different than we’ve done in the past,” said NIF tour coordinator CaT Vogen. “The students received an overview of what happens at NIF,” she said. “But also, by giving a personalized touch in addition to describing what they’re seeing on the tour route, we wanted them to feel very comfortable engaging with the docents and asking personal questions connected to STEM.”

Students get a closeup view of NIF targets from STEM Day docents Becky Butlin, target fabrication interface manager (left), and Lila Ahrendes, target fabrication engineer.

Students get a closeup view of NIF targets from STEM Day docents Becky Butlin, target fabrication interface manager (left), and Lila Ahrendes, target fabrication engineer. Interested in safety and security as a student, and after pursuing a degree in administration of justice, Vogen now helps ensure that events like STEM Day are smooth-running and safe for all participants.

Every week she coordinates an average of 10 NIF tours, which range from visiting dignitaries to school groups to outside scientists partnering with LLNL. She is responsible for matching tour groups with the best guide and working around NIF’s busy shot schedule.

Staffing booths in the plaza outside the facility, docents covered the basics of NIF’s operation, missions, and groundbreaking achievements.

The students got hands-on experience with how a laser works and were given their own diffraction gratings. By holding them up like monocle eyepieces, they explored color components by looking at different sources of light.

Students look through diffraction gratings to examine properties of light.

Students look through diffraction gratings to examine properties of light. The docents stationed inside NIF along the tour route, from the Master Oscillator Room (MOR) to the cavernous Laser Bay 1, changed up the usual tour script as well. This time, the docents also reflected on how STEM inspired them as students and guided their personal “beampaths” to NIF.

The MOR is where the NIF action starts, generating the light that ultimately is amplified a quadrillion times before it hits the target. Target diagnostics engineer Nathan Palmer said his circuitous path to NIF began after he received his Ph.D. in plasma physics. Standing in front of the small coil of laser light, Palmer talked about the MOR and told the students the story of how he got to NIF.

“While a graduate student in the 1990s, I was aware of the plans for NIF,” said Palmer, who as a child had a clear understanding that he wanted a career in science. “People were excited by it. I thought it would be a cool place to work, but I doubted that I’d ever get the chance to work there.

“After my degree, I started working for the medical device industry and then later with x-ray equipment. I gravitated toward engineering because I liked being more hands-on with the hardware.”

When an opportunity at NIF opened in 2010, Palmer jumped at it. Now he specializes in measuring the performance of NIF experiments by engineering high-speed x-ray imaging diagnostics.

In front of NIF’s Master Oscillator Room, STEM Day docent Nathan Palmer reveals how NIF’s laser begins as a tiny pulse of light.

In front of NIF’s Master Oscillator Room, STEM Day docent Nathan Palmer reveals how NIF’s laser begins as a tiny pulse of light. At another station, Software Application Team lead Arsenia Rendon told students about the systems and computer codes running in NIF’s Control Room. After she described how NASA’s Mission Control inspired the room’s design of the room, she said building things was her inspiration.

“My grandfather was in construction, and he had a lot of lumber around,” Rendon said. “I liked to build things with it, like little houses. Translating that into software development, I now build applications.”

Rendon said she related to some of the challenges faced by the students and encouraged them to study hard and keep pushing upward.

“I was the first in my family to go to college,” she said. “I went to a great school, USC, and I got my MBA afterwards. I wanted to let the students know that this could happen for them. Just because you were born in a certain place and because you were raised in a certain environment, that doesn’t dictate who you can become.”

As eighth-graders from the Central Valley explore the science and technology of NIF, they also learn about some of the many paths that STEM can open for them.

As eighth-graders from the Central Valley explore the science and technology of NIF, they also learn about some of the many paths that STEM can open for them. After visiting the booths and touring NIF, a group of eighth-grade students gathered to talk about the STEM Day activities that most inspired them and ponder what they’d like to do in the future.

“Anything about space is very interesting to me,” said Anureet. “Just thinking about if there can be life other than us is very interesting.”

“I like space and anything to do with it,” added Sania. “When I grow up, I want to become a galactic astronomer. I asked for a telescope for my birthday.”

Zoey’s interests are a little closer to Earth. “I liked the hands-on experiments and when we went inside NIF and looked around at the laser,” she said.

Christian, who codes in class, enjoyed learning about coding at NIF and said, “I liked the laser, especially the Control Room.”

Impressed most by the engineering that went into NIF, Joshua said, “I like how they spent so much to time to build something for the future of humankind.”

“Science and robotics and explosives,” added Nancy with a smile. “Everything here looks so cool.”

These students and others at Livermore for STEM Day were at the right place to trigger their imaginations, not just about what science and technology is possible, but also seeing themselves helping make it happen—maybe even at a place that does what stars do.

NIF’s STEM Day team included Lila Ahrendes, Connor Amorin, Matthew Barberis, Becky Butlin, Thomas Galvin, Sylwia Hamilton, Denise Hoover, John Jett, Kenneth Kasper, Laura Kegelmeyer, Derrick Lassle, Zhi Liao, Dan Linehan, Emily Link, Mark Meamber, Nathan Palmer, Arsenia Rendon, Steven Ross, Kendra Ruiz, Stefano Schiaffino, Swanee Shin, Matt Snyder, Scott Trummer, CaT Vogen, and Karl Wilhelmsen.

—Dan Linehan

Follow us on Twitter: @lasers_llnl

Looking Back on a Mammoth Discovery

In December 1997, workers at the NIF construction site were surprised with an early holiday gift. While removing 210,000 cubic yards of earth—enough to fill 2½ Olympic-size swimming pools—for a utility trench some 30 feet below ground level, they unearthed the bones of a prehistoric mammoth. The remains included a partial skull, jawbone, vertebrae, and a tusk.

Paleontologist C. Bruce Hanson excavates the mammoth bones in 1998. Credit: LLNL archives.

Paleontologist C. Bruce Hanson excavates the mammoth bones in 1998. Credit: LLNL archives. Experts from the University of California were called in, and samples were sent to LLNL’s Center for Mass Spectrometry for analysis and dating. A preliminary investigation by University of California, Berkeley paleontologist Mark Goodwin estimated the bones to be more than 10,000 years old (later dated at 16,000 years old).

Excavation of the bones required expert oversight, and the Lab contracted a team, headed by paleontologist C. Bruce Hanson, to extract the bones for preservation and study. The excavation team worked carefully to expose and clean the mammoth, applying a hardening varnish to seal the cracks and stabilize the bones.

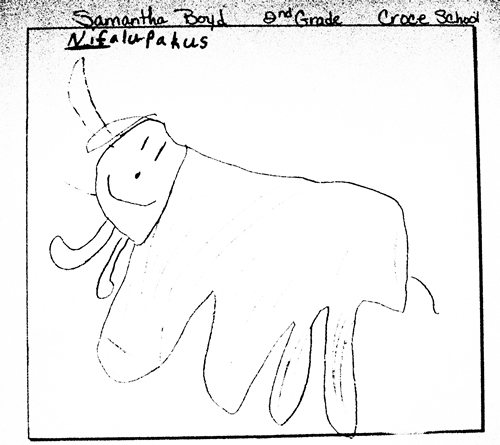

Second grader Samantha Boyd’s winning drawing for the “Name-the-Mammoth Contest” in 1998.

Second grader Samantha Boyd’s winning drawing for the “Name-the-Mammoth Contest” in 1998. To prepare the mammoth for removal, they wrapped the bones with a layer of moistened tissue paper, followed by strips of burlap dipped into plaster for safe transport to University of California, Berkeley’s Museum of Paleontology. Two weeks after the initial find, another bone cluster was unearthed some 15 feet from the original discovery site—including ribs and an almost complete humerus, or shoulder bone.

According to paleontologists, mammoths were actually quite common to this area; and, as such, the discovery of the bones at the NIF construction site didn’t come as a complete surprise. According to Goodwin, however,the NIF find was significant, as it was a more complete mammoth skeleton than is usually found.

So too, per lead paleontologist C. Bruce Hanson, the ancient mammoth excavated from NIF’s construction site most likely had plenty of company, including at least one other mammal that apparently had made a meal of the mammoth. Tooth marks on the bones suggested to Hanson that a dire wolf or saber-toothed tiger may have killed the ancient mammoth.

The mammoth bones became a part of the permanent collection at the UC Museum of Paleontology in Berkeley.

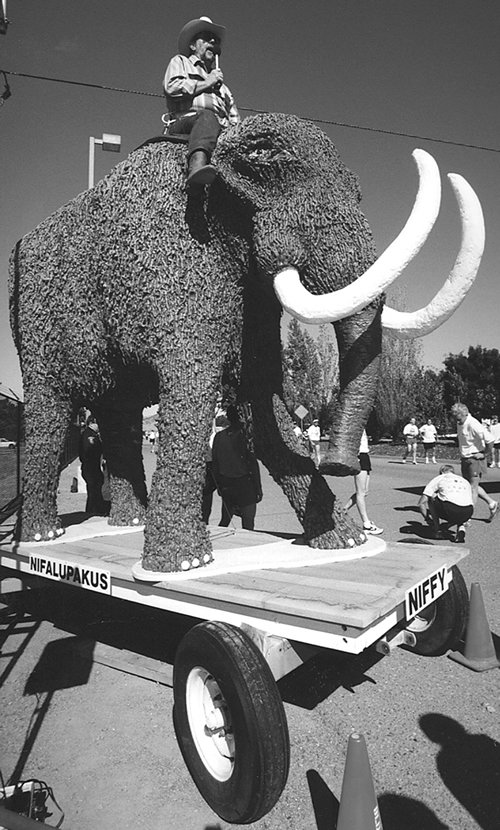

Deputy Director for Operations Bob Kuckuck kicks off the Lab’s 1998 Run for Home atop Niffy.

Deputy Director for Operations Bob Kuckuck kicks off the Lab’s 1998 Run for Home atop Niffy. Of course, this wasn’t the first discovery of ancient bones at LLNL. On Oct. 30, 1974, Lab employee Chips McPherson discovered the foreleg of a mastodon, estimated to be 1 million years old, at Site 300 in Tracy, Calif. In that instance, days of heavy rain, rather than construction work, revealed the bone sticking out of a road embankment.

In practical terms, the discovery of the mammoth’s bones caused no real impact to LLNL operations, as NIF construction stayed on schedule throughout the excavation. The discovery, however, generated a great deal of excitement and interest among Lab employees and throughout the local community—making 1998 the year of the mammoth at the Lab.

Tapping into the excitement behind the prehistoric find, the Lab sponsored a local contest in March 1998 for Livermore school children to name the mammoth. The “Name-The-Mammoth Contest” invited elementary children to come up with a name and, depending on grade-level, either draw a picture or write a paragraph extolling the virtues of the selected name.

The grand prize winner was seven-year old Samantha Boyd, who came up with “Nifalupakus,” or “Niffy” for short.

“Niffy,” in manifest plaster form, would go on to feature in several Lab-sponsored events throughout the remainder of the year. To celebrate the City of Livermore’s 80th annual rodeo parade, carpenters within the Plant Engineering Shops donated their time to create a life-sized Niffy replica to feature as a float in the parade. Later that year, Niffy made a further appearance, this time at the Lab’s annual “Run for Home” event, with Deputy Director for Operations Bob Kuckuck perched atop the beast to kick off the race.

—Jeffrey Sahaida

Follow us on Twitter: @lasers_llnl