NIF Laser Diodes Reduce Stress in Metal 3-D Printed Parts

July 15, 2019

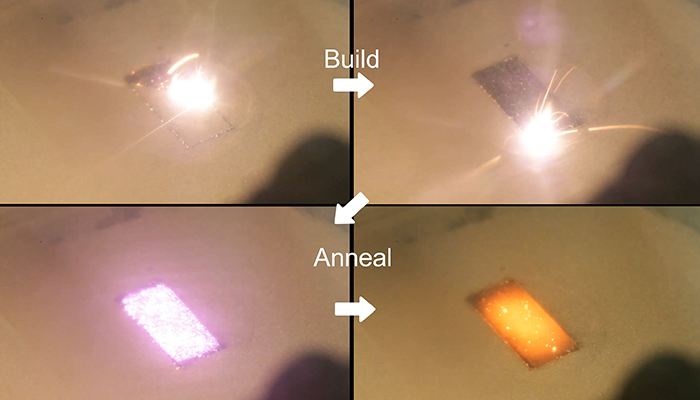

This image shows the process of building and annealing a rectangular block of 316L stainless steel. The first and second panels are the focused scanning laser melting the powder layer into the underlying part. The third panel is the diode turning on and illuminating the surface of the part to heat and anneal it. The last panel is right after the diode turns off, showing the block is at high temperature (more than 950°C).

This image shows the process of building and annealing a rectangular block of 316L stainless steel. The first and second panels are the focused scanning laser melting the powder layer into the underlying part. The third panel is the diode turning on and illuminating the surface of the part to heat and anneal it. The last panel is right after the diode turns off, showing the block is at high temperature (more than 950°C). In 3-D printing, residual stress can build up in parts during the printing process due to the expansion of heated material and contraction of cold material. This can generate forces that can distort the part and cause cracks that can weaken or even tear it to pieces, especially in metals.

Researchers at LLNL and the University of California, Davis are addressing the problem by using laser diodes—high-powered lasers borrowed from technology created for NIF—to rapidly heat the printed layers during a build.

The new technique, described in a paper released online by the journal Additive Manufacturing, resulted in the reduction of effective residual stress in metal 3D-printed test parts by 90 percent. The technique enabled researchers to reduce temperature gradients (the difference between hot and cold extremes) and control cooling rates.

“In metals, it’s really hard to overcome these stresses,” said materials scientist John Roehling, the paper’s lead author. “There’s been a lot of work on trying to do things like changing the scanning strategy to redistribute the residual stresses, but basically our approach was to get rid of them as we’re building the part, so you don’t have any of those problems. Using this approach, we can effectively get rid of residual stresses to the point that you don’t have part failures during the build anymore.”

For the study, LLNL engineer and co-lead author Will Smith built small, bridge-like structures from 316L stainless steel using the laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) process. Smith let each layer solidify before illuminating their surfaces with the diodes, initially at full power and immediately ramping down the intensity over a period of 20 seconds. The result was akin to putting the part in a furnace after each layer as surface temperatures reached about 1,000 degrees Centigrade (1,832 degrees Fahrenheit).

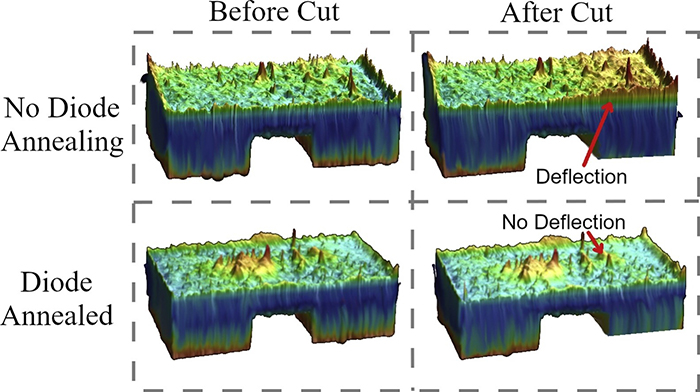

The finished parts, with their thick legs and thin overhang section, allowed researchers to measure how much residual stress was relieved by cutting one of the legs off and analyzing how much the weaker overhang section moved. When the diodes were used, the bridge didn’t deflect anymore, researchers said.

LLNL and UC Davis researchers included this graphical abstract that shows the results of their paper published in Additive Manufacturing.

LLNL and UC Davis researchers included this graphical abstract that shows the results of their paper published in Additive Manufacturing. “Building the parts was similar to how a normal metal 3D printer works,” Smith said, “but the novel part of our machine is we use a secondary laser that projects over a larger area and that post-heats the part afterwards—it raises the temperature up rapidly and slowly cools it down in a controlled fashion.

“When we used the diodes, we saw that there was a trend in the reduction of residual stress, and it compared to what is done traditionally by annealing a part in an oven afterwards. This was a good result, and it was promising as to how effective our technique was.”The approach is an offshoot of a previous project in which laser diodes, developed to smooth out lasers in NIF, were used to 3D-print entire metal layers in one shot. It bests other common methods for reducing residual stress in metal parts, such as altering the scanning strategy or using a heated build plate, Roehling said. Because the approach heats from the top, there’s no limit on the height of the parts.

Researchers will next perform a more in-depth study, turning their attention to increasing the number of layers per heating cycle to see if they can reduce residual stress to the same degree, attempt more complex parts, and use more quantitative techniques to gain a more in-depth understanding of the process.

“This technology is something that could be scaled up, because right now we’re projecting over a relatively small area and there’s still a lot of room for improvement,” Smith said. “By adding more of the diode lasers, we could add more heating area if someone wanted to integrate this into a system with a larger printing area.”

More importantly, Roehling said, researchers will explore controlling phase transformations in titanium alloy (Ti64). Typically, when building with Ti64, phase transformation causes the metal to become extremely brittle, causing parts to crack. If researchers could avoid the transformation by cooling the part slowly, it could make the material ductile enough to meet aerospace standards, said Roehling, who added that preliminary results are promising.

The project was funded through the Laboratory Directed Research and Development (LDRD) program. Co-authors included LLNL researchers Gabe Guss, Tien Roehling, Bey Vrancken, Joe McKeown and Ibo Matthews, as well as UC Davis professor Michael Hill.

-Jeremy Thomas

Follow us on Twitter: @lasers_llnl