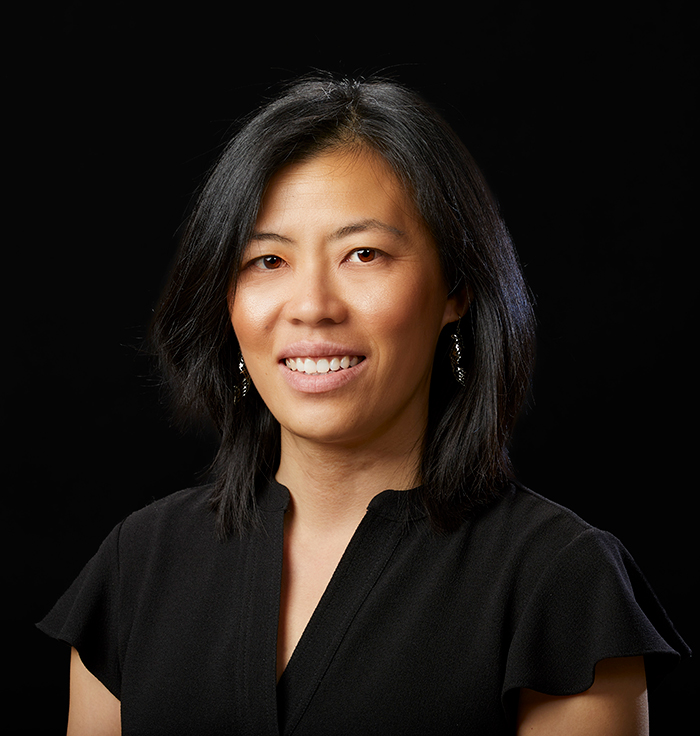

Tammy Ma

Paying It Forward Has Paid Career Dividends

LLNL physicist Tammy Ma, the keynote speaker at a March 2019 Young Women’s Conference in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM), snaps a selfie with conference organizer Deedee Ortiz onstage at Princeton University’s Richmond Auditorium. Credit: Elle Starkman, Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory

LLNL physicist Tammy Ma, the keynote speaker at a March 2019 Young Women’s Conference in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM), snaps a selfie with conference organizer Deedee Ortiz onstage at Princeton University’s Richmond Auditorium. Credit: Elle Starkman, Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) physicist Tammy Ma says she learned a valuable lesson in 2001 when she was a summer intern at the Laboratory.

At that time, Ma was so thankful for her mentor’s help and advice that she offered to pay for dinner. The mentor declined and told her: “No, let me pay. When you have students, you pay, and pass it on.”

Ma took the advice to heart and paying it forward has since become a recurrent theme that goes far beyond picking up dinner tabs. Whether it’s reaching out to students, colleagues, VIPs, members of Congress, and the media, giving YouTube and TED talks, or speaking at conferences and symposiums across the nation and around the world, Ma continues to pay it forward with a passion for communicating the knowledge she’s gained throughout her exceptional career as an experimental plasma physicist at LLNL.

She is currently the program element leader for High-Intensity Laser High Energy Density (HED) Science-Advanced Photon Technologies, and associate program leader for HED Laboratory Plasmas. She also leads the Lab’s Inertial Fusion Energy (IFE) Institutional Initiative.

Because of LLNL’s historic fusion ignition milestone on Dec. 5, 2022, at the National Ignition Facility (NIF), Ma says now is the right time to share the importance of fusion energy research to the nation and the world.

“With the recent ignition result, it’s really exhilarating that people care about science,” Ma said during a keynote speech at a recent meeting of the Asian Pacific American Council (APAC), one of LLNL’s employee resource groups.

“We’re trying to take advantage of that to get the message out about ignition, about fusion energy, where we want to push the field. It’s an opportunity. We want to try to capitalize on that excitement right now to grow this new inertial fusion energy (IFE) program in the United States. If you don’t communicate about the importance of what we’ve just done, how would people know? It’s incumbent on us to share that knowledge and get people excited.”

A Chance for Sharing

Growing up in the East Bay city of Fremont, Ma credited her parents for making “enormous sacrifices” for their children.

“Neither of them were scientists, but they love science and they passed that passion on to me and my brother, who also happens to be a physicist,” she says. “They did their best. They took us to museums. We talked about news that had any science in it. But you don’t really know what it means to be a physicist or what research really means. I think I kind of just fell into it from high school. I enjoyed my science classes the most.”

Ma received her bachelor’s degree in aerospace engineering from Caltech in 2005 and earned her master’s degree in 2008 and Ph.D. in 2010, both from the University of California, San Diego. She joined LLNL as a postdoc in 2010 and as a staff scientist in 2012.

Ma won a 2013 Presidential Early Career Award for Science and Engineering, the highest honor bestowed by the U.S. government on science and engineering professionals in the early stages of their independent research careers, and a prestigious Department of Energy Office of Science Early Career Research Program award in 2018.

Earlier this year, the Krell Institute, a nonprofit group serving the scientific and educational communities, honored Ma with its James Corones Award in Leadership, Community Building, and Communication.

A Passion for Communicating

She discovered the importance of STEM education at a young age when her parents took her to “Science on Saturday,” LLNL’s science lecture series for middle and high school students.

“That was what really got me excited and I learned a ton there,” she says. “I feel that I have to give back. It’s also just incredibly rewarding to me. I really enjoy working with students and young people.”

Her passion about science communications and outreach led to the most impactful decisions in her career.

“That actually laid the groundwork for me in my current role, which is not as technical as I originally intended my career to be,” she says. “I’ve gone into a lot more policy and advocacy and figuring out how to talk to Congress members or VIPs when they come and visit. How do you pass on a message to them that is succinct but tells them the importance and the impact of the work we do to make sure that we continue to get funded or grow programs that we need?”

Among her many hats, Ma heads a group that works with universities and other institutions to advance the use of the world’s highest-intensity lasers for research into matter, astrophysics, fusion, and other subjects. With the Lab’s IFE Initiative, she helps guide foundational fusion energy studies at LLNL and in the wider community to support the DOE’s drive to commercialize fusion energy.

Ma has helped build the HED and fusion communities, including establishing the IFE Virtual Collaboratory to encourage connections between private and public fusion programs. Among her many other activities, she serves on the DOE’s Fusion Energy Sciences (FES) Advisory Committee, and in 2020 helped author a long-range plan for U.S. efforts in this area. She recently chaired for FES the IFE basic research needs study, which will inform the national IFE strategy.

Ma said over $5 billion of private investment has gone into developing fusion energy for the past couple of years, with most of that going into magnetic fusion energy companies, and about $200 million of that being invested in IFE. She estimated that commercialization of a full-scale power plant won’t happen for another 10 to 20 years, and that’s dependent on overall investment and commitment from the government.

“(U.S. Energy) Secretary (Jennifer) Granholm said we have to pursue multiple pathways right now,” Ma says. “We don’t know which one is going to be the winner, and the benefits and advantages of fusion are so huge if we can actually realize it. If we’re serious about harnessing fusion, we should be trying everything we can to make it happen.”

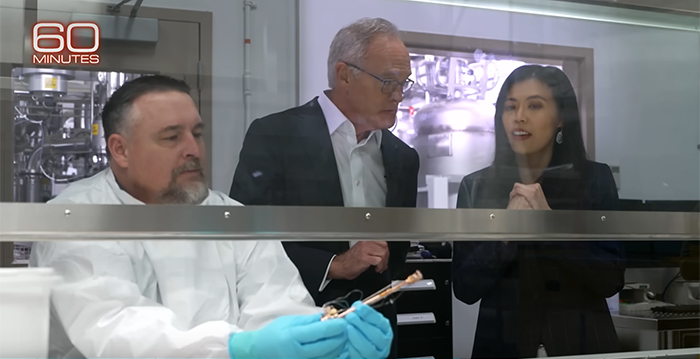

Tammy Ma and journalist Scott Pelley (center) view what Pelley said was “what’s left of the target assembly that changed history” during an episode of the CBS-TV news program “60 Minutes” that was broadcast on Jan. 15, 2023.

Tammy Ma and journalist Scott Pelley (center) view what Pelley said was “what’s left of the target assembly that changed history” during an episode of the CBS-TV news program “60 Minutes” that was broadcast on Jan. 15, 2023. Ma has said that she loves working at LLNL because “we do science with a purpose.

“It’s all really big science—it’s not one single scientist in his or her own little lab that can figure it out,” she says. “You need big teams and a lot of resources and you need support from the scientific community and the government, and you get all that here. Hopefully what we do has a positive impact on society and human life.”

As for the key people who’ve influenced her as a physicist, Ma credited a number of mentors at LLNL over the years—along with her mother, with whom she talks every day.

“I share with her my struggles and frustrations, and it’s so nice to have someone to share that with and to have encouragement,” she says. “She helps me make good decisions.

“When I was deciding which role I should take at the Lab and if I should apply for a new position that was opening up, my mom actually watched one of my YouTube talks and said, ‘You have to do fusion energy for the Lab, you have to do it.’ And that influenced where I decided to take my career.”

—Jon Kawamoto

July 12, 2023

Video: Tammy Ma describes the lure of cutting-edge science, the enjoyment of collaborating with world-class researchers at a national laboratory, the anticipation while waiting for the results of an experiment—and her ambition to become an astronaut.